Two recent papers on model interpretability

2016-04-12Update 2018-09-09: if you're interested in the topic of this post, you might enjoy the talk I gave at QCon.ai in April 2018, which is a much deeper look based on work we did at Fast Forward Labs.

Machine learning often involves a trade-off between accuracy and interpretability. Models that are easy to understand perform poorly, while models that perform well tend to be hard to understand. This can be a show-stopper in many contexts.

It can be risky or legally dubious to deploy a model you don’t understand in a commercial environment.

Interpreting a model is often the whole point of using machine learning in science. A random forest that outputs correct predictions about the world but offers no insight into the mechanisms involved is not much use.

And using uninterpretable models in medicine can even be life-threatening. A 2015 KDD paper by Rich Caruana and colleagues from Microsoft Research has a story that illustrates this clearly and is worth quoting in full:

The system learned the rule

HasAsthama(x) ⇒ LowerRisk(x), i.e., that patients with pneumonia who have a history of asthma have lower risk of dying from pneumonia than the general population. Needless to say, this rule is counterintuitive. But it reflected a true pattern in the training data: patients with a history of asthma who presented with pneumonia usually were admitted not only to the hospital but directly to the ICU (Intensive Care Unit). The good news is that the aggressive care received by asthmatic pneumonia patients was so effective that it lowered their risk of dying from pneumonia compared to the general population. The bad news is that because the prognosis for these patients is better than average, models trained on the data incorrectly learn that asthma lowers risk, when in fact asthmatics have much higher risk (if not hospitalized).

Experts can spot these problems in models they can scrutinize, but that’s not easy for the best-performing models, such as random forests and recurrent neural networks.

This post is about two recent publications that take very different approaches to this problem: the first paper introduces a new kind of particularly interpretable model, while the second provides a framework for getting “explanations” from arbitrary models.

Bayesian Rule Lists

It’s usually difficult to explain a classifier by just showing what a model looks like, because the models are enormous, inscrutable matrices. But Bayesian Rule Lists are so simple you can understand how they work by simply writing a model down.

Here’s a fully specified BRL classifier for the well-known Titanic dataset, for which the task is to predict whether a Titanic passenger survived based on their gender, age, and ticket class:

IF male AND adult THEN survival probability: 21% (19% - 23%)

ELSE IF 3rd class THEN survival probability: 44% (38% - 51%)

ELSE IF 1st class THEN survival probability: 96% (92% - 99%)

ELSE survival probability: 88% (82% - 94%)

If you’ve seen decisions trees, BRLs will look familiar. In fact, as Benjamin Letham and his co-authors at MIT point out in the paper, any decision tree can be expressed as a decision list, and any decision list is a one-sided decision tree.

BRLs are interpretability taken to its extreme, but without necessarily sacrificing accuracy. The paper shows examples where BRLs perform comparably to random forests.

The paper focusses on the clinical setting, where metrics like the AGPAR score, which are easy to calculate and easy to reason about, are invaluable. They propose a BRL alternative to a commonly used, but somewhat poorly performing score used to predict stroke risk:

IF hemiplegia AND age > 60 then stroke risk 58.9% (53.8%–63.8%)

ELSE IF cerebrovascular disorder then stroke risk 47.8% (44.8%–50.7%)

ELSE IF transient ischaemic attack then stroke risk 23.8% (19.5%–28.4%)

ELSE IF occlusion AND stenosis of carotid artery without infarction then

stroke risk 15.8% (12.2%–19.6%)

ELSE IF altered state of consciousness AND age > 60 then stroke risk

16.0% (12.2%–20.2%)

ELSE IF age ≤ 70 then stroke risk 4.6% (3.9%–5.4%)

ELSE stroke risk 8.7% (7.9%–9.6%)

The practical matter of how BRLs are trained is covered in the paper too. As the name suggests, they are hierarchical probabilistic models. This Bayesian ancestry is presumably why BRLs come with confidence intervals, which are intrinsically useful for prediction, but also further aid interpretability.

And the good news is there’s a Python implementation with a scikit-learn-like API.

Local interpretable model-agnostic explanations

To get the interpretability benefits of BRLs you naturally have to use BRL models. But if you have engineering or other reasons to stick with a different model, this may not be an option.

If your the law, the product, or your tolerance for commercial risk requires interpretability then there is no avoiding the hard work of figuring out in an ad hoc way how to interpret the behaviour of your particular model.

It would be much better to have framework that could be applied whatever the model. This is what Marco Tulio Ribeiro and collaborators attempt to build in their recent paper on local interpretable model-agnostic explanations. These model-agnostic “explanations” are reached in what is effectively a post-processing step that can come after any kind of model.

Quoting from the project’s github page:

Intuitively, an “explanation” is a local linear approximation of the model’s behaviour. While the model may be very complex globally, it is easier to approximate it around the vicinity of a particular instance. While treating the model as a black box, we perturb the instance we want to explain and learn a sparse linear model around it, as an explanation.

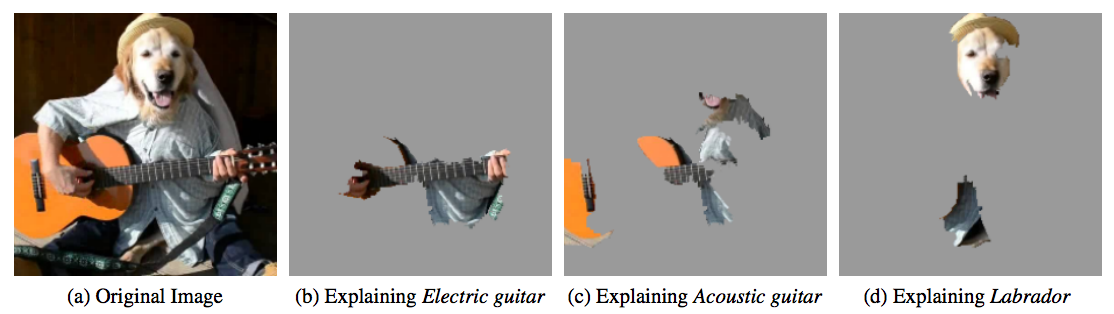

Put another way, by perturbing the input, it’s possible to determine which parts are responsible for the end result. The output of this kind of analysis might be something like this impressive figure taken from the paper, which shows the “parts” of the image responsible for its classification by a convolutional neural network.

Incidentally, this “explanation” shows one of the situations in which interpretability is most valuable: when the classification is incorrect. Misclassifications inevitably reduce trust in a system, but that can be somewhat mitigated by an explanation. Sometimes, if you can tell a user why you got something wrong, that’s the next best thing to getting it right!

I haven’t played with LIME in detail, and I’m not sure how well it would perform where the explanation for a classification is a non-local or holistic characteristic of the input. Nevertheless, it’s very exciting!

For more, there is a conceptual discussion in Riberio’s blog, and a Python implementation with the usual scikit-learn-like API.